The Story Behind Howard Nichols, the Limestone Barn-Builder

Howard Nichols in front of his house, with wife Lizzie close behind, circa 1923.

Howard Nichols of Limestone, Maine, built the largest barn in Maine and possibly in all of New England in the 1920s, only to see that and a second barn burn to the ground—in addition to other farm buildings that also caught on fire.

How did Howard survive, and who was he, really?

Almost a century before, Joseph Nichols married Nancy Lewis in Digby, Nova Scotia. They soon moved west to Digby Corner in the parish of Wilmot, New Brunswick, just east of the US/Canadian border and Bridgewater, Maine.

George Howard, child number 10, was born in 1868. Perhaps having so many older siblings molded him into a determined boy. He never learned how to read or write. Instead, he worked on his parents’ farm, learning how to cultivate crops and take care of the livestock.

In 1890 when he was 22, Howard, who seemed to prefer his middle name, received permission from neighbors James and Millie Carmichael to marry their daughter, Maggie, who was just 15. Howard was still farming with his father, and after the marriage, he and Maggie lived at his parents’ house.

By then most of Howard’s siblings had moved on, with several settling in the US. His brother, Richard, left that same year for Maine. Sisters Marmaree Good, Hettie McCleary, and Frances Lewis also settled across the border. Only sisters Caroline and Lottie were still at home.

Settling West

Maggie’s first child, Hattie Ann, was born in 1893, and the following year, Howard, Joseph, and their families packed up and moved to Maine.

The town of Fort Fairfield, with a population of about 3,500, is divided in two by the sparkling Aroostook River. Five miles northeast of the river, farmer Calvin S. Rich sold his 161-acre homestead lot on the Center Limestone Road to Howard for $3,200.

Maggie had barely settled into her new home when she found out that she was pregnant again. Joseph Harold came into the world on December 17, and baby Olive came in 1895 but died of cholera when she was only eight months old. Eliza Jane was born in September, 1897, and Mary Helen followed just a year later.

Right across the road from the Nichols family lived farmer and widower Leverett Kimball, also from New Brunswick. In early 1898 he married Lizzie Savage, a Fort school teacher who had grown up in Wilmot and graduated from a teacher’s college. Another Wilmot native, Joseph A. Emery, immigrated to Fort Fairfield in 1897 and took up farming on the same road.

Some years before, Lizzie’s parents, Howard’s parents, Joe Emery’s parents, Maggie’s parents, and the Pryors (related to Maggie’s mother) had all farmed in Wilmot.

Having Lizzie just across the road might have been a comfort to Maggie as they seemed to have a lot in common. Both were about the same age. Both were Methodists. Both had young families. And Maggie’s mother, as a child, lived next door to Lizzie’s father and his parents.

While Maggie was busy raising children, Howard was busy buying up more farmland. He eventually owned farms in Washburn, southwest of Fort Fairfield, and Mars Hill, next to Bridgewater. Land he bought in Limestone, however, a few miles north of the Fort farm, eventually became his greatest achievement.

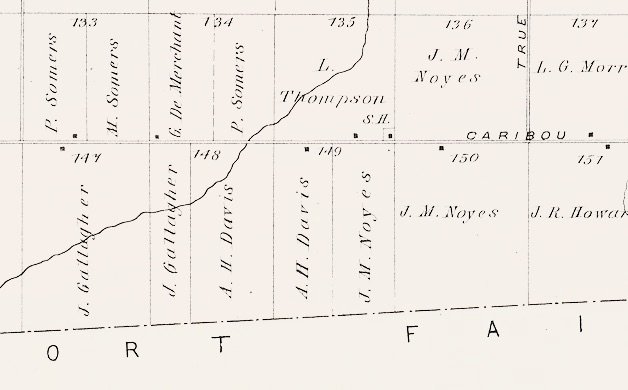

A portion of a Limestone map, 1877.

For example, Howard bought one Limestone 100-acre property—the east portion of Lot 149—on July 22, 1899. He paid Josiah M. Noyes a total of $2,050. The lot bordered the Noyes homestead farm on the Noyes Road, which ran parallel to Fort Fairfield’s townline, and became part of Howard’s eventual showcase farm.

After Howard and Maggie’s daughter Mary Helen died on September 11 of that year, the Nichols’ moved to Limestone.

Joseph and Nancy lived in their own quarters and kept a servant, John Dickinson. But by 1902, the couple were staying with relatives in Bridgewater. It was there in November that Joseph had a stroke and died. Sometime after the funeral, Nancy returned to Limestone.

Darker Times

After his father’s death, things seemed to change for Howard. About a year later, on Dec. 14, 1903, a divorce he had filed against Maggie was finalized. The document stated that she had treated him cruelly and abusively.

Back then, there had to be a specific reason, such as abandonment, cruelty, or adultery, for a divorce to occur. Perhaps Maggie was indeed cruel to Howard. Or perhaps, because she did not abandon him or commit adultery, the cruelty clause had to be used for the divorce to take place, regardless of whether the claim was real.

Not to leave any dust under his feet, Howard married again three months later to Lizzie Adams, 22, of Limestone, a native of Hartland, N.B.

Hattie Snow Clark

The marriage record stated that this was Lizzie’s first marriage and the second for Howard. But other records show that Lizzie had married Bridgewater-native David Snow on Aug. 15, 1900, in Hartland. There’s some indication that daughter Hattie was born of this union in Madison, Minnesota, around 1901, and that David died there in 1921.

As a teenager, Hattie worked as a servant in Limestone. She married William Van Tassel in 1920, with the marriage record stating that her parents were Lizzie Adams and David Snow. She later married Ephrain Clark and resided in Ontario, Canada.

Nine months after Howard and Lizzie’s marriage took place, Nancy Nichols, 78, died in Limestone from pneumonia. According to the Fort Fairfield Review’s Bridgewater news, “Mrs. Maggie Nichols returned from Fort Fairfield (to Bridgewater) where she had been called by the death of her mother-in-law.” Apparently Maggie was not totally banned from the Nichols family, even though her children remained with Howard and his second wife.

In January, 1905, Howard and Lizzie Nichols’ first child, Mansy, came into the world but died in October of enterocolitis. In 1910, Lizzie gave birth to her first son, Henry Richard, and in the spring of 1913, John William was born. Two days after John’s birth, Lizzie’s younger brother, Amos, married her stepdaughter, Eliza Jane. Another daughter, Mammie, was born in May, 1915, but died in October from cholera.

Lizzie gave birth to Frances in October, 1917, and delivered Howard Nichols Junior on July 4,1918. An unnamed baby, born in 1919, died the next day.

The Divorced Wife

Meanwhile, Maggie Nichols was a servant on the James and Olive Thornbush farm on the Houlton Road in Fort Fairfield. Around the same time, Leverett and Lizzie Kimball moved from their Center Limestone Road property to a farm on the Presque Isle Road, not far from the Thornbushes. Perhaps the closeness of the two former neighbors was pure coincidence. Or maybe Lizzie Kimball had something to do with Maggie being hired on the nearby farm.

Dr. Herrick Kimball

In February, 1910, Lizzie’s husband died unexpectedly from pneumonia. Leverett left his pregnant wife with four young children to raise, in addition to a stepson. She never remarried but maintained the farm and raised her children. Sadly, her fifth child, a son born after Leverett’s death, died a few months later.

As was the case in those days, neighbors and friends would console and help a young widow after her husband’s untimely death. Perhaps Maggie Nichols had something to do with heping her old neighbor as well.

With Lizzie’s support and possibly help from others, her son Herrick eventually graduated from medical school and became a well-known doctor and surgeon in northeastern Maine. Dr. Kimball based his practice in Fort Fairfield until his death in 1966.

During World War I, Howard and Maggie’s eldest son, Joseph, registered for the draft. At the time he was a farmer in Caswell, next to Limestone. Responding to the registration question, “Have you a relative depended on you for support?,” Joseph stated that his mother depended on him and he asked for an exemption from the draft. There’s no record that he actually did have to serve.

The property next to Howard’s in Limestone was the 1870 Noyes farm. Here, in the early 1900s, Charles and Nettie Noyes, their children and friends, and farm workers stand outside.

By the time Joseph married Olga Olson of Caswell in 1919, the marriage record stated that his mother was working as a housekeeper in Bridgewater. The Bridewater farm, owned by Joseph and Alberta Smith, was located on Snow Settlement Road, not far from the Canadian border and Maggie’s mother, who lived in New Brunswick.

In January, 1922, Millie Carmichael died. “A kind and generous woman,” her obituary stated. Only three floral arrangements were listed: a spray from the family, a lily from a Bridgewater friend, and a bouquet of white carnations sent by Lizzie Kimball of Fort Fairfield.

Two years later Maggie married William Scott, a widower and long-time Bridgewater farmer. This was the last recorded information about Maggie.

The Golden Years

C.C. Harvey

Also during World War I, there was a national shortage of potatoes. Prices for Maine potatoes spiked and growers like Howard Nichols reaped the benefits.

Beginning in 1920, Howard’s name appeared more frequently in the Review, owned and edited by C.C. Harvey. Nothing was sacred in that paper as seen in the May 12, 1920, edition under the heading: “That Potato Money.”

The newspaper reported that Howard visited the Limestone Trust Company and deposited $19,000, which in today’s market would have the purchasing power of $291,409. The next day, he deposited $10,000. Two of his sons deposited about $1,800 that they earned from harvesting just over two acres of potatoes.

So it’s little wonder that Howard took advantage of the good years in potato farming and built his family a fine house on the Noyes Road farm that was, according to the Review, “almost a marvel in its convenience, capacity and quality of materials and workmanship.”

The William Ward farm on the Ward Road, Limestone, early 1900s. William is standing by the team of horses and potato digger.

Around this time, Howard’s nearby neighbor, William Ward, built a very large barn. Howard decided that he wanted to build one bigger.

As the Presque Isle Star-Herald explained, “The successful farmer up this way has one vice—a desire to put all his money into something that will show.”

In the fall of 1921, local newspapers reported that Howard, one of the largest farmers in Limestone, had planted 104 acres in potatoes and “has been turning the tubers out of the ground at a rapid rate…One day he dug 900 barrels,” (each full barrel weighed 165 pounds). “But probably the record made last Friday is as good or better than any other day…he dug exactly 65 barrels in 25 minutes, the potatoes seeming to hop out of the ground like popcorn out of the popper.”

The Saga of the Barns

That same year Howard designed his new barn, which was completed for the most part in 1922. He had electricity and air conditioning installed in the seven-storied structure with its stained glass windows and two huge weathervanes covered with gold.

In the summer of 1923, hundreds of folks, each paying twenty-five cents to tour the farm buildings, visited on weekends. Several hundred dollars could be made a week from the fees and postcards sold by Lizzie. People also attended Sunday afternoon and evening “religious meetings” held in the giant barn.

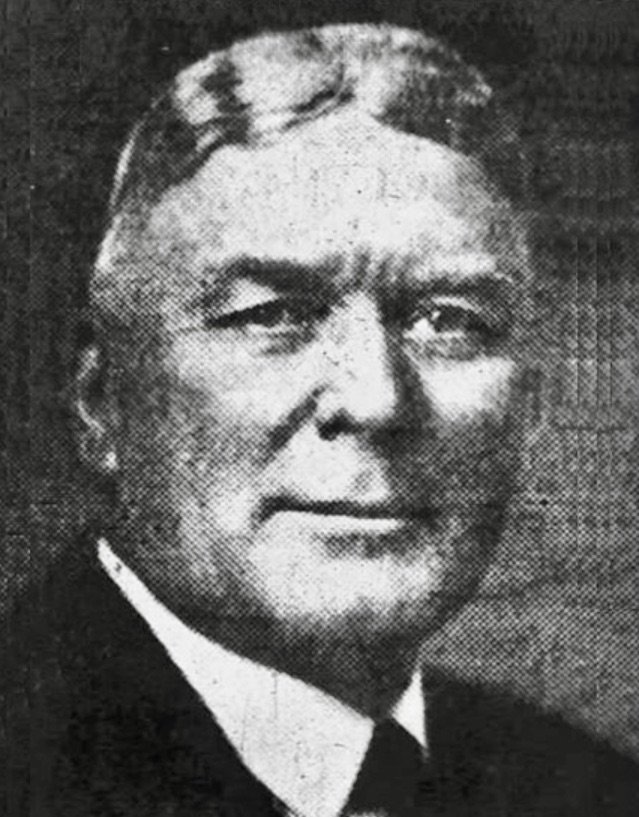

G. Howard Nichols

Then on that fateful windy day in March,1924, the glorious barn and connected house burned to the ground. Only Lizzie, who was “sick in bed,” and the children were at home. The loss was estimated at $90,000. Howard had only $12,000 in insurance.

Howard and family moved temporarily to the boarding house of the Charles Noyes starch factory. The son of Josiah, Charles lived next door to Howard on the Noyes family farm.

Five days after the fire, Lizzie went into labor and another Nichols was born. The baby’s sex and name were never recorded, however, and the child died the following day.

Not one to broadcast his family woes, Howard did tell the Review later that March that he was determined to rebuild the structures as they were before. To do so “with such extraordinary excellence certainly stamps him as a man of splendid pluck and courage,” Harvey wrote.

Fortunately, the concrete walls and steel-reinforced floor under the barn, unaffected by the fire, were “as good as new,” the Review reported, as well as the underground passageway—blasted through ledge—that went from the road to the barn cellar—wide enough for a team of horses to turn around in.

It wasn’t until April, 1925, that construction began on the second barn. By the middle of July, the new structure was almost finished at a cost of $47,000. “It is a fine building, comparing well with the barn burned,” the Review surmised.

Lizzie Adams Nichols

More Changes at Home

Then on a Sunday in April, 1926, Alice Elizabeth “Lizzie” Nichols, 42, “took a bad spell,” the Review reported, and “died quite suddenly at 12:30 a.m. Monday.” Another column stated that she died of “heart trouble.” Her newest baby, Christina, was just 10 months old.

The funeral was held at the Limestone Grange Hall church with Evangelist Lee Good of Monticello and the Rev. Benjamin Bubar of Blaine officiating. Pall bearers were all neighbors of the Nichols family: Norman Gallagher, Elwood Noyes (Charles’ son), Benjamin Ward (William’s son), and Waldo Spear.

“Mrs. Nichols was a hard-working woman and will be greatly missed,” the obituary stated.

Howard, by now 58, faced with several children still at home, didn’t waste time in acquiring a wife. She had to be, it seemed, from New Brunswick.

Margaret Jane Marshall, 43, had been married twice before and was the mother of three daughters. At the time she and Howard married in 1926, she was working as a housekeeper in Fielding, N.B. On August 20, Margaret immigrated to the US, accompanied by two of her daughters. According to border information, she was sponsored by Howard Nichols, “a friend,” and was described as having a medium complexion, gray hair and gray eyes.

The view today looking west towards the city of Caribou, on the Noyes Road next to Howard’s former farm.

More Fires

Things were quiet in the Nichols family until the following year when on November 10 another fire reportedly started with kerosene and a match. The tragedy "wiped me out again,” Howard said.

The flames began around 11 p.m. and the barn and house were soon consumed. According to the Review, the fire “got a great headway before warning was given” and the buildings “burned flat.”

This time, the loss was estimate at $65,000, with insurance only at $10,000. Hay, grain, machinery, horses, pigs, and thoroughbred cattle were also lost.

“The best barn in New England owned by one man, not a corporation,” the Review said. “General opinion is that the fire was incendiary.”

Two weeks later, Howard lost his granary and its contents by fire, a loss initially estimated at $30,000.

Howard said he “knew who did it.”

Ever determined, he commenced construction on a third set of buildings in 1928. The barn was built on the same cellar with the tunnel to the road, only it wasn’t as tall or grand as the first and was valued at $15,000.

Frances Nichols

By 1930, Howard’s daughter Jannie and his second wife’s brother, Amos Adams, had six kids and were farming in Washburn. His son, Joseph, worked on a farm in Caswell. Still living on Howard’s Limestone farm were John, 17, Frances, 12, Junior, 11, Christina, 4, and Madge, 10, Margaret’s daughter.

In the July 27, 1933, issue of the Review, Howard’s letter to C.C. Harvey described another fire.

“I came near losing all my buildings again Monday afternoon, July 24, in the thunder and lightening storm,” Howard began. “The lightening came in on the wire coming out of a socket where there should have been a bulb, in the peak of the barn, and only a platform of straw.

“A fire started and two hired men were still working down below. The fire dropped down 15 feet to where they were moving the straw. They called out for help and soon 10 workers were battling the flames.

“Water had to be carried in pails up two flights of stairs and then handed up to the scaffold from one person to another,” Howard said. “By this time there were two fires to put out—one about 30 feet high and the other 45 feet high. By having lots of water on hand, and through the faithful work of the men, the fire was soon under control and all the buildings and contents saved.

“If the barn had burned this time,” he concluded, “I would not have tried to build again.”

Hardships in Later Years

Howard with one of his grandchildren.

Although fire did not plague Howard again, he still had other worries. In 1939 he was in danger of losing his Limestone farm by foreclosure. The Great Depression had deepened, and potato prices in the mid-1930s were as low as 42 cents per 165 pounds, compared to mid-1920s prices of $5 or more.

Howard “met his 1939 demand…just in the nick of time and so everything is safe until next season,” Harvey wrote. If his 125 acres of spuds yielded well and prices were fair, “he will have no trouble in keeping the wolf away from the door again.”

Eventually, however, Howard and Margaret moved back to Fort Fairfield in 1944 and took up farming on the Currier Road. By now Howard was 76 years old. Either through additional farm hardships or just wanting to downsize, it seems he no longer owned as much land. The Limestone farm was not mentioned again, nor his farm in Washburn.

King Harvey

In 1946, Kingdon “King” Harvey, the late C.C. Harvey’s son and newspaper successor, reported that Howard had hired a man to cut down 11 acres of stumps and brush on his Fort farm for $220. The man cut them all except for one stump that contained a hornets’ nest. “Mr. Nichols chided him for being so bashful,” Harvey wrote, “and the man offered him $5 if he would take it out.”

The next morning before dawn, Howard “dumped some kerosene on the nest, waited a short time…then operated successfully on the stump. He would have enjoyed doing the whole 11 acres at the same rate of pay.”

Although Howard remained in Fort Fairfield for the rest of his life, things were not always rosy. In December 1948, he again dictated a letter to the Review.

“I rented all the potato land I had—57 acres. Forty-three acres I had on the Mars Hill farm and the rest of the goal I used on the farm in Fort Fairfield. I got $960 rent, and my taxes on the Fort Fairfield farm were $929.25, which left me $30.75 to run me until 1949. The quicker I move out of Fort Fairfield the better. I’m past 80 years old. Now I will have to work out by day to make a living.”

Gone were the glory days of a large farming operation. But still, Howard continued on, even though his physical health was in decline.

Howard in later years.

Not all was work on the farm, however. George Leavitt of Limestone visited Howard for several days in March,1952. On a Sunday morning the two climbed a big hill covered with a thick crust of snow. The men, the Review reported, decided to “have a slide on Mr. Nichols’ hand sled…Mr. Nichols in front steering and Mr. Leavitt on behind, each one with a cane.”

John Adams, Howard’s grandson, “came out with a camera and took their pictures. It was hardly safe for these ‘young boys’ to go sliding down that big hill. Mr. Nichols is nearly 84 years old and Mr. Leavitt is 92.”

Old Farmers Never Retire

When Howard was 85, he conveyed to Harvey in January, 1953, that he wanted to tell his readers what a farmer did all winter.

He said that he handled all the winter chores by himself, tending seven cows, 19 hogs, two horses, 39 sheep, and 24 hens. He also split wood for the cookstove and furnace, kept a fire in the potato house, and lugged potatoes from that building to feed the animals.

“Not bad at all for a man who has hardening of the arteries and some days finds it hard to even walk,” Harvey wrote. “He began working for himself 67 years ago and now he’s hoofing it all alone—just he and his wife.

“He had a hired man last fall,” Harvey continued, but after he sold most of his crop, paid his expenses and the hire man, he “did not have a dollar left,” so he had to do his own work.

Looking east on the Noyes Road towards the former Charles Noyes property.

Such work eventually caught up to the aging farmer and by June he become ill. Just six months later, on December 23, Howard died.

“He had been a farmer all his life and was known all over the country for having built three of the largest and finest barns in Aroostook County,” Harvey wrote. “People coming from long distances to see one of them, which cost a large sum of money and which was destroyed by fire quite a number of years ago. But Mr. Nichols never lost courage.”

The Former Limestone Farm Today

Howard’s third barn in Limestone—smaller than the first two but still containing the tunnel underneath—is remembered by some folks who, in decades past, watched trucks drive through the cellar and turn around inside. But now that barn is also gone. A modern farm shop, owned by Smith’s Farm Inc., stands in its place.

Smith’s Farm Shop, on an elevation where the Nichols’ buildings once stood.

Smith’s Farm began in Mars Hill in the 1800s. Today, with its Stag brand, the family-run company grows and ships broccoli, cauliflower, and potatoes all along the eastern seaboard. The company also handles oats and barley for Quaker Oats.

As a forward-thinking farmer, Howard, no doubt, would be impressed.

And the grand, old buildings? The shape of the land still hints of their past existence and of the accomplishments of a long ago farmer full of determination and courage.