Bucksport, Maine: Memories of the Distant Past

Misty view of the famous Fort Knox and Penobscot River.

A great way to get acquainted with historic Bucksport is to take a stroll in the fog down its waterfront walkway—just under a mile along the shore of the Penobscot River—and then take a turn onto Main Street, heading east to where you began.

Things are hazy when the fog rolls in, and landmarks take on an air of mystery. With all the fog, you’d never know the tallest public bridge observatory in the world is right there across the river in nearby Stockton. The Penobscot Narrows Bridge is home to the Penobscot Narrows Observatory. On a foggy morning in Bucksport, you can only imagine the graceful lines of the modern bridge and its towers.

Another landmark half hidden in the mist is Fort Knox, one of the best preserved forts in the United States. Now a state historic park, the fort was named after Major General Henry Knox, who lived his later years in Thomaston. Construction on the fort began in 1844 and was the first built in Maine entirely of granite. On a clearer day, a trip to the park is a must see as many of its dark corners are readily available for discoveries.

Bucksport was famous for years as the home to a large paper mill, located on Indian Point. You can see parts of the Point, through the fog, where commercial buildings, including a blue one, still stand.

The Point was so named after early Native Americans who once had a burial ground there. It was here in 1891 that the first archaeological dig in the country was conducted by Harvard Archaeologist Charles Willoughby. A red pigment and bone fragments were unearthed at the site.

The so-called Red Paint People buried their dead with large amounts of red ochre—a clay substance containing ferric oxide. No one knows why the red pigment was so important to them, nor why the people eventually disappeared. Since colonial times, local farmers had found pockets of the pigment, not naturally found in Maine, in their fields.

Red ochre

The Red People hunted swordfish along the coast, made unusual tools, and lived in various areas of the northeast between 3,000-1,000 B.C.E.

Leaving the mist of ancient history behind, turn onto Main Street and you will discover many old buildings, as Bucksport was founded in the 1700s. Among the earlier gems is a stunning house built in the 1850s, designed by a man of many talents.

The Linwood Cottage sits on a small hill and is a mix of Greek Revival, Gothic Revival, and Italianate styles. Its first owner and designer was the town’s jeweler and watch repairman, James Emery, a Belfast native who lived in Bucksport for most of his life and died there in 1899.

Emery’s house was the first Maine structure to be featured in a national magazine in 1855. The cottage remained in the Emery family for years and was operated as a funeral home by the 1940s. The lovely structure has since returned to a private home owner and is listed on the National Register of Historic Places for architectural significance.

Although the house looks cheerful, the Emery family had many heartaches early on. Emery’s first wife, the former Matilda Hervey, and their three children all had died by 1852. The following year he married Caroline Hervey, who was perhaps Matilda’s sister. Three of their six children survived to adulthood.

An example of James Emery’s oil paintings from the 1880s.

Emery, a successful businessman, played a role in the founding of the Bucksport Theological Seminary. He also designed several other buildings in the state and painted seascapes. A portrait of George Washington by Emery, recently restored, hangs in the town council chamber. Several of Emery’s works are also on display at the Mariners Museum in Virginia.

Further along on Main Street is the 1887 Buck Memorial Library, constructed of Blue Hill granite and designed by Blue Hill native and Boston architect George Clough. The library was a gift from the family of Richard Pike Buck, a grandson of Bucksport’s founder and a New York businessman. After his death, his wife and family carried out his wishes to fund the construction of a library in his hometown.

The Gothic Revival structure was placed on the National Registry of Historical Places in 1987, and its interior heart pine woodwork is original.

You can’t get very far from the Buck family’s influence in Bucksport, which originally was called Buckstown. Further up Main Street from the library, across from a grocery store, is the remarkable corner lot of Buck Cemetery.

A foggy day is the perfect time to visit the cemetery, which is fenced off but has a nice winding walkway where you can view the most important stone in town, the Buck Memorial.

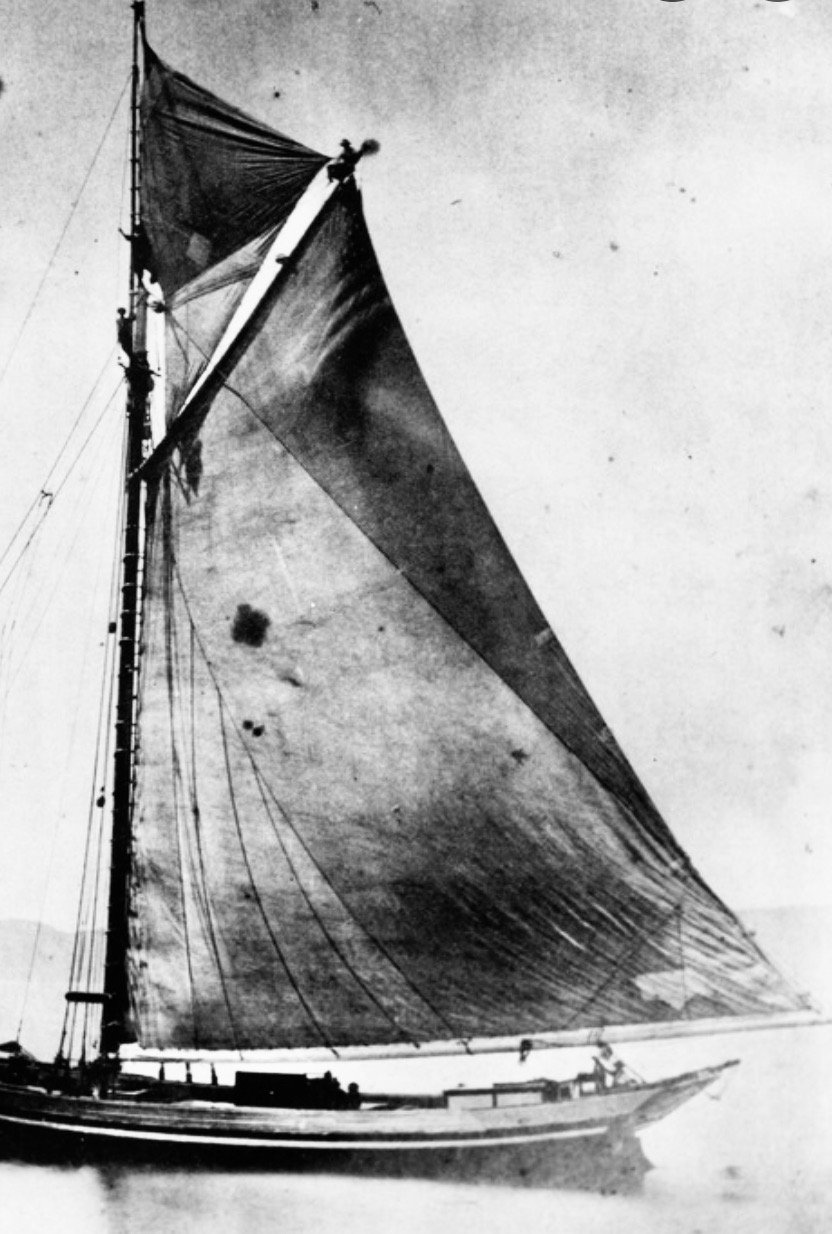

Picture in your mind a sloop—a ship with a single sail—traveling up the Penobscot River through the coastal mist. Such a boat was owned and operated by Captain Jonathan Cornelius Buck, a Massachusetts native, who sailed the Sally up the river in July of 1762 to survey six Maine plantations—later named Bucksport, Orland, Castine, Sedgwick, Blue Hill, and Surry.

Buck made another trip the the following year and in 1764, along with other townsmen from Haverhill, Massachusetts, he began the construction of a settlement in Plantation 1.

During the American Revolutionary War, Buck was colonel of the Fifth Militia Regiment of Lincoln County, Massachusetts, and was considered a “patriot.” He was known for his strong opinions, good memory, and “steadfast purpose.”

Grave trouble came to the young Maine settlement during the summer of 1779, after a horrific river blockade was created by the British, which cut off the settlers’ supplies. British war ships chased American patriots up the river towards Bangor. There, the Americans sunk their own ships rather than have the Red Coats take control. It was considered the worst navel defeat, prior to Pearl Harbor, in American history.

Afterward, Plantation 1 residents fled from their hiding places in the woods and walked some 200 miles back to Haverhill.

Meanwhile, the British burned the settlers’ Maine properties, including Buck’s saw mill and other buildings. After the 1783 peace treaty, many of the residents, including Buck, returned and rebuilt. In 1789, the folks named the town Buckstown in honor of the colonel.

Buck died in 1795, and his descendants had a granite monument built in his honor in the 1850s.

Some of his relations are buried in the same cemetery. He and his wife, the former Lydia Morse, had six children who reached adulthood: Jonathan Jr., Mary, Ebenezer, Amos, Daniel, and Lydia.

The Jonathan Buck memorial area includes plaques explaining his honored life and the ridiculous legend.

When the 1850s granite marker was exposed to coastal, damp weather, a stain or flaw appeared, possibly from oxidation. The stain resembled the shape of a woman’s foot and lower leg. Soon stories began circulating that a curse had been put on Mr. Buck for his sentencing of a supposed witch to be burned. As she was being consumed by flames, she cursed him. Then a portion of her leg fell off and rolled beyond the fire. Part of her curse claimed that her “sign” would remain on his tombstone.

Mr. Buck’s original 1795 tombstone, much smaller than the 1850s memorial, never had such an imprint, and no record of witch burning exists in Maine. Thus, the “curse” and mysterious foot outline don’t make any sense. The legends were formed to help explain a strange but harmless image on the front of the larger stone.

Despite the supposed curse, the Buck family made many contributions to the town of Bucksport, but not many images of these early settlers remain.

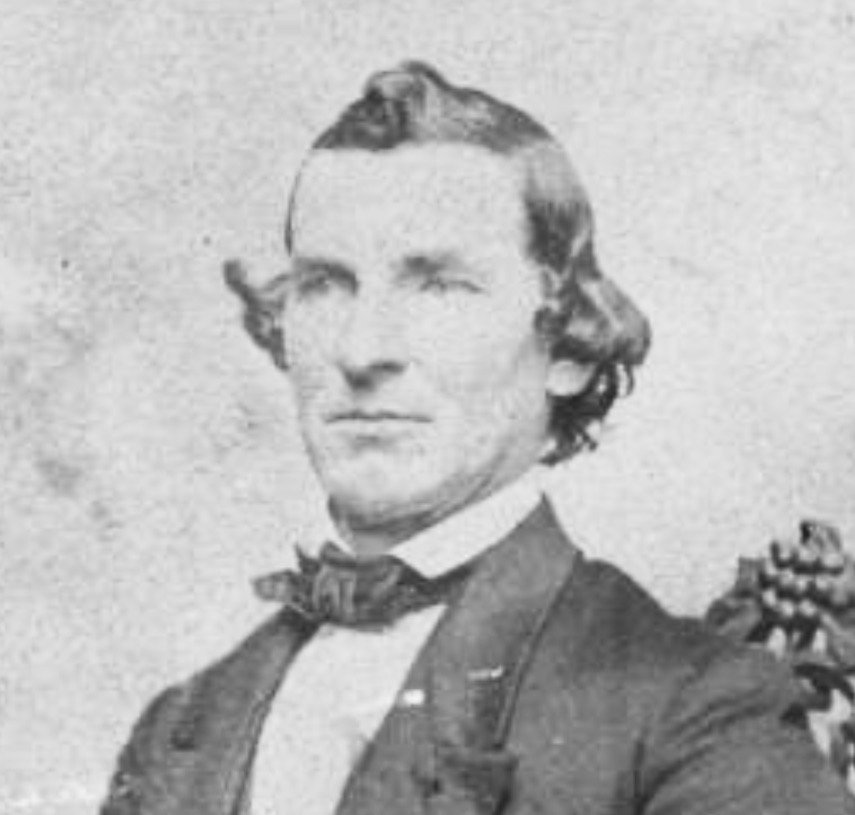

Joseph Buck

Jonathan Buck Jr., who also sailed with his father up the Penobscot in the sloop Sally, had a son, Joseph, who became a well-known ship builder in the community. Joseph’s mother was Hannah Gale, and he married Abigail Hill in 1811. Joseph died in 1853, around the same time as the above memorial was installed in the cemetery.

A photograph of Joseph is still in existence. He indeed appears just like you’d imagine a strong, coastal settler to look, back in the almost forgotten days of early Bucksport.

And so, next time you discover a foggy day on the coast of Maine, a nice, misty walk along the paths of Bucksport might be an experience you’d enjoy.