Gangster Al Brady: Why No One Claimed His Body

The FBI’s most wanted criminal was gunned down on Central Street in Bangor, Maine, on Columbus Day in 1937, but no one—including relatives from Al Brady’s home state of Indiana—claimed his body for burial.

So Bangor officials took matters into their own hands. After preserving Brady’s brain in a jar housed at a local hospital, they buried him in a simple casket in a remote corner of the city lot in Mount Hope Cemetery. Although Brady had stolen lots of money and goods from across the Midwest over the past several years, on October 15 he received the burial of a pauper, and his graved was left unmarked.

Prior to that fateful shooting, Brady, Clarence Lee Shaffer Jr., and James Dalhover had purchased several guns and ammo at Dakin’s Sporting Goods Store. They were expected to returned a third time in a week or so for a Thompson submachine gun they had ordered from the clerk.

But instead, after their second visit and placement of the Tommy gun order that autumn, store owner Shep Hurd alerted the police who in turn alerted the FBI. Over a dozen agents congregated in the area, along with state and local police, waiting for the Buick with Ohio plates to come back to town.

Early on October 12, the Buick parked just down from the store with Brady in the back seat. Dalhover entered the building and was immediately handcuffed. At that moment Shaffer, who was guarding the front entrance, started firing. Agents returned fire and the gangster fell into the street, dead. Two agents then approached Brady, who said not to shoot as he was coming out. But he came out of the car shooting and fell dead in the middle of the street.

Al Brady, front, on Central Street in downtown Bangor.

Shaffer’s family claimed his body, but no one claimed Brady’s. Did he still have relatives back in Indiana who wanted to ignore him or was everyone close to him, friend or relative, dead too?

The story goes that Brady experienced a rather normal childhood in Indiana. But what’s normal?

His mother, Zelia Clara Portwood, like the rest of her family, was born in Kentucky but moved to Washington, Indiana, when she was very young. She had four older brothers and was the only daughter of Joseph and Phoebe. In 1908 when she was 17, she married Daniel Leroy Brady, the eldest child of Daniel J. and Prudence (Knight) Brady of Iroquois, IN.

Daniel was a laborer at the Indiana Terra Cotta Mill. He and Zelia’s firstborn, Earnest Dale, lived for about a month before his death in 1909. A year later, Alfred James was born on October 25.

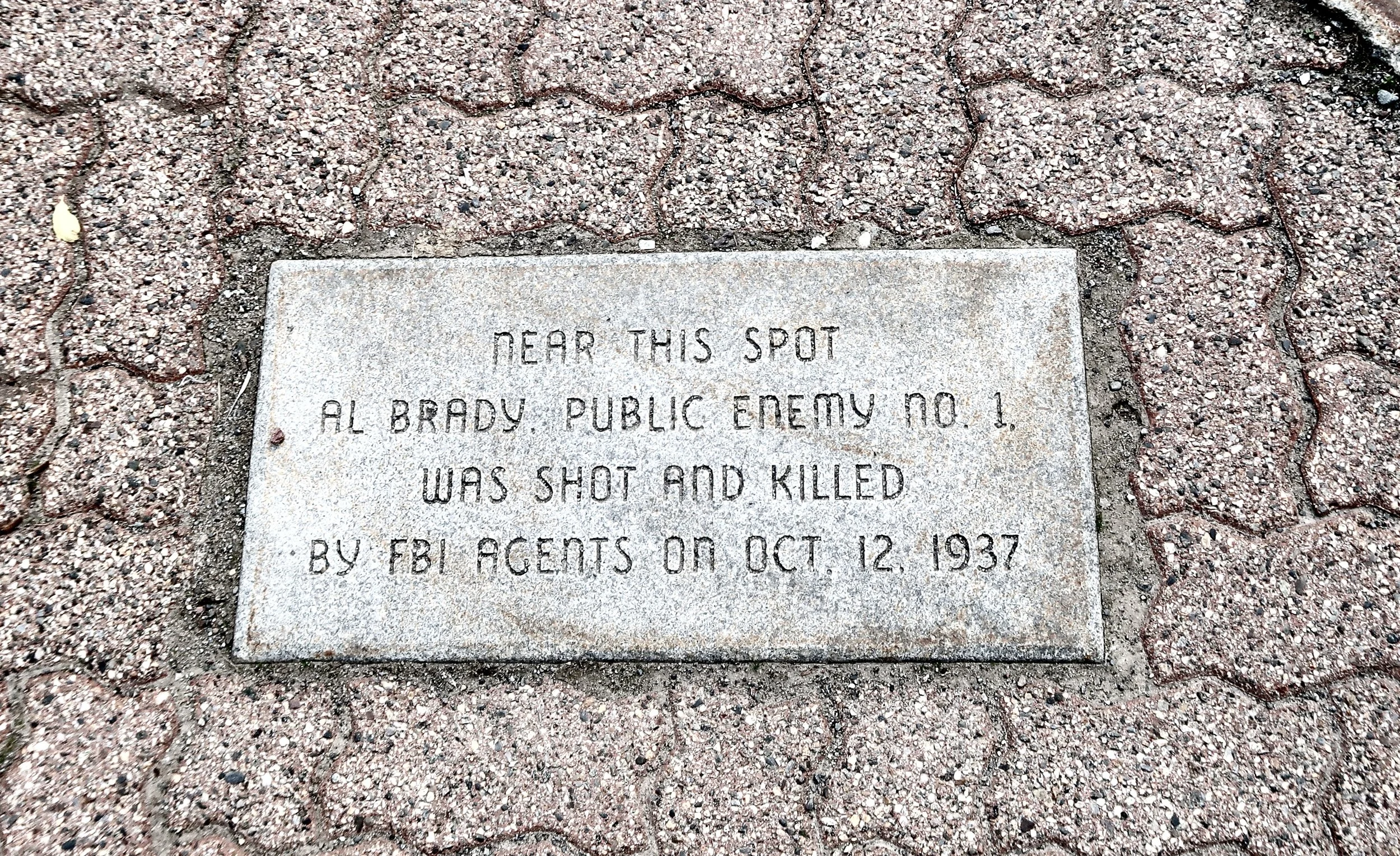

A plaque in the pavement marks the area near where Brady fell in Bangor.

The couple then divorced and Zelia married Herman Philip Richert in early 1913. Richert was also a laborer and had married Minnie Voyles in Indiana in the 1890s, but the couple had later divorced.

If Zelia had waited a few months before remarrying, she would have had the title of widow, instead. That August her former husband was in a terrible accident involving a “portable engine” which apparently blew up. Daniel Brady, 27, was pronounced dead with injuries to both his head and body.

By early 1917, Zelia and Richert’s marriage had also ended in divorce. On Valentine’s Day she married John R. Biddle, 55, in Chicago.

It was perhaps at this time in young Al Brady’s life that things were relatively normal. His stepdad farmed in Center, IN. The family was small, with only the stepdad, mother, and Brady. Zelia did not have any more children. Perhaps as Brady grew older, he worked on the farm as well. Although his maternal grandparents were still living, his paternal grandparents were both deceased by 1923.

The Central Street plaque.

In late 1924, the family dynamics changed yet again. Biddle, 62, died at 9 a.m. on October 20 at Eel River, IN, from a gunshot wound. An inquest was held and authorities concluded that the shooting was “probably accidental.” We don’t know if suicide was suspected or if either Al Brady or his mother were involved. Rumors flew, with some saying that Biddle might have been abusive and that Zelia or Brady had pulled the trigger.

Records are sketchy after that, but there is one record of Clara Zella Biddle marrying James Mikles Brady on August 1, 1925, in Indiana. The marriage certificate stated that he lived in Danville and his parents, Joseph and Belle, were from Ireland.

Shep Hurd, Dakin’s owner who received the FBI’s $1,500 reward.

Another record—the 1910 Chicago census—stated a James M. Brady, 19, was a laborer working in the “Clay Hole” at the city’s House of Correction. He was the only Brady listed there, among hundreds of other inmates.

But that’s as far as it goes. There’s no record of James Mikles Brady’s death or what happened to him after 1925, although there’s a possibility he took a boat to Honolulu in 1926.

In the Indianapolis directory for 1929, Al Brady, 19, and his mother were living on East 11th Street, with no reference to another stepfather. Brady at that time was working as a “machine operator” and Zelia Clara kept house.

Sadly, Clara, as she was often called, was in the hospital for several days before dying on the morning of September 11 from acute Bright’s Disease. She was 37. She also had ovarian “tumors.” Her son was the informant for her death certificate information. He stated that her last name was Biddle and that she was a widow.

Area of the former Dakin store with the Briar Patch bookstore, left, and 11 Central eatery located in the next building.

Two months later, Brady’s maternal grandmother, Phoebe Portwood, died in Brook, IN.

In 1930, Brady was a boarder on North Handing Street in Indianapolis with the Wells family. Both Ira and Gertrude Wells were Kentucky natives, so perhaps there was a connection to Brady’s mother and her Kentucky roots. Brady, at that time, worked as a painter for an automobile body plant.

Kenduskeag Stream and Norumbega Parkway on Central Street.

Several years later, Clara Biddle’s father, Joseph, died, and Al Brady was left with no surviving parents or grandparents except for his former stepfather, Herman Richert, who was living in New Albany. By then, Brady had joined up with Shaffer and Dalhover, robbed stores and banks in the Midwest, and killed several people, including police officers.

FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover issued a $1,500 reward to anyone with knowledge of the whereabouts of America’s most wanted gang, but still Brady eluded police and agents. Eventually the gang hid out in Connecticut and were told that it was easier to buy weapons and ammunition in Maine where there were more hunters, more woods than people, and fewer questions.

The gang visited Bangor one time too many in 1937 and proved that Mainers were not that easily fooled. They told Dakin’s clerk that they were buying guns to hunt with, but the clerk knew those weapons weren’t the kind used for shooting game.

Sharp-shooter Walter Walsh, 1938.

Around the time of Brady’s death, his mother’s four older brothers and their families were still residing in or near Indiana, as well as two of his father’s sisters and two brothers. Yet none of them wanted anything to do with burying their nephew.

I guess we can’t blame them. The Great Depression years were hard economically for most Americans. The expense of burying their nephew was probably a burden, not to mention the shame connected to his name.

Brady’s grave in Bangor remained almost forgotten until the early 2000s when some folks began talking about reenacting the shootout on its 50th anniversary. They wanted to honor the brave people who had taken down the criminals, including the FBI sharp-shooter injured twice in the gun fight, 100-year-old Walter Walsh.

Anonymous flowers are frequently left at his grave.

As part of that anniversary, a local merchant donated a simple stone to mark Brady’s grave and his connection to history. It was not meant as an honor to Brady, but as a documentation of what happened.

Since then other reenactments have taken place, cementing the memory of Bangor’s part in ending the reign of terror. The simple grave for Brady also showed that giving even a criminal a basic burial and headstone was “doing the right thing.”